This morning, 68-year-old Maria (who wishes to remain anonymous) is scheduled to do a video interview with Anne-Marie Benharoun. In a tired voice she explains that she can’t get the software to work: “Since my operations my brain no longer functions”, whispers the pensioner. The appointment is therefore made by telephone.

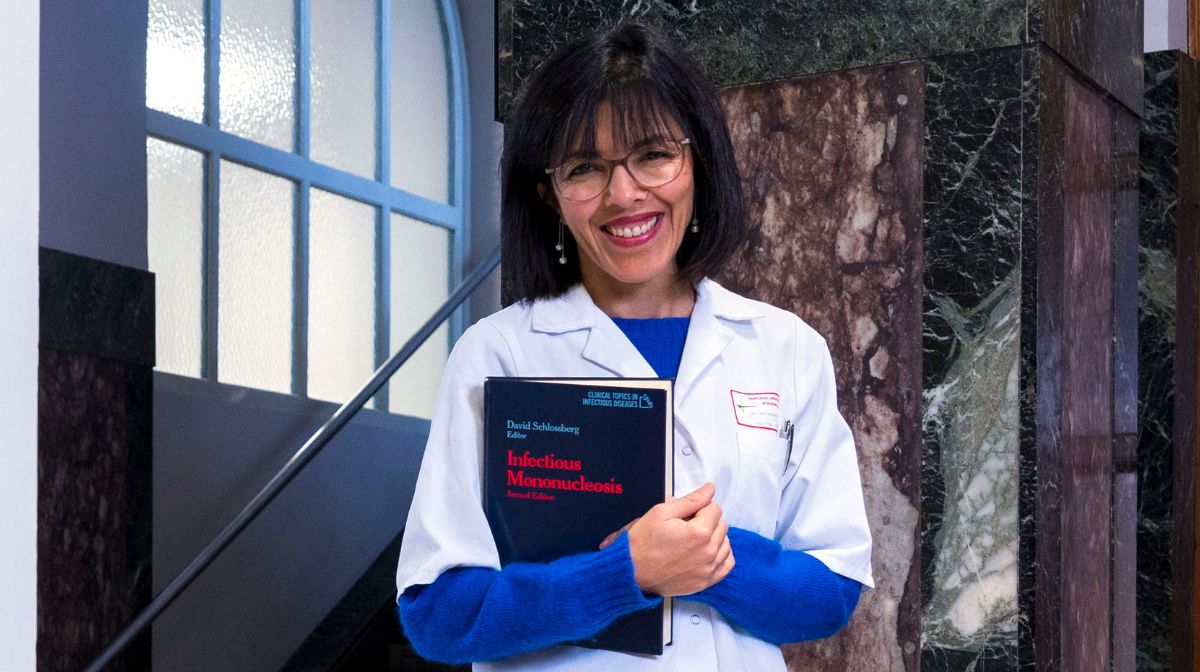

Maria talks somewhat incoherently about the three years of treatments, pain and torment that have passed since she was diagnosed with breast cancer. “It’s normal to be exhausted: you’ve had three general anesthetics in a very short space of time, which is very traumatic for the body. I experienced this too, for different reasons than yours. It’s hard to get back on track., assures his interlocutor. Anne-Marie Benharoun is neither a doctor nor a psychologist: as a “patient partner,” she draws her knowledge primarily from her experiences, from the breast cancer ordeal she endured in 2014. For an hour-long conversation, she resorts to telling her story to build a bond with Maria and try to understand the consequences of the disease on her daily life.

Value their experience

Still little known in France, patient partners began to appear in the Anglo-Saxon world, particularly in Canada, at the end of the 20th century.e Century. They appeared in France in the early 2000s. As volunteers or employees, they are mobilized in associations and in the oncology or diabetology departments of private or public institutions in Lille, Bordeaux, Lyon or Paris to inform patients, lead workshops or help caregivers prepare certain announcements. Since 2009 there has even been a special training course, the University of Patients-Sorbonne, linked to the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris. Every year, 75 students suffering from a chronic illness learn how to use their experiences to benefit other patients.

Since her cancer, Anne-Marie Benharoun, 52 years old, with large round glasses and short-cropped red hair, still lives with fatigue and pain every day. By listening to patients’ problems, she created the service she would have needed at the time: “When I had my breasts removed I was completely unprepared for the terrible shock of the visual result. I would have liked to have spoken to another patient first to find out.”remembers the former trainer for professional care, who gradually gave up her job to devote more time to patients.

You still have 65% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.